Sacred Stones of the Inca

I've come across some interesting material about Inca (Inka?) views of sacred landscape, rocks in particular. The first part is from a piece entitled Dialogue with Sacred Landscape: Inka Framing Expressions by Ruth Anne Phillips. It's a little long, but facinating.

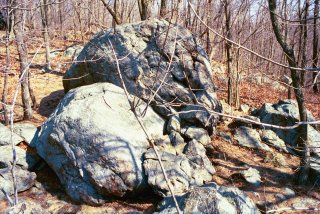

"Stones played particularly important roles in Inka mythology as they could suddenly be called to action to help their human counterparts, even turning into humans themselves. One story recounts rocks on a battlefield rising up as warriors at a particularly perilous moment in the fight to help the Inka soldiers defeat their enemy. According to Susan Niles, 'Origin myths tell of founding ancestors emerging from the earth, being converted to stone, and remaining for all time as tangible proof of the story.' Rebecca Stone-Miller writes:

'The Inkas felt a special interchangeability with stones, believing them to be alive and able to transform into people and vice versa. . . . Inka stonework seems alive as it dynamically responds to natural formations, creates active surfaces, and dances in the strong light of the high-altitude sun. At the same time, this dynamic Inka feeling of identity with stone led them to manipulate stones, mountains, and streams toward imperial expressive ends. Being one with the earth, they proclaimed themselves able to construct cultural statements with its materials and preexisting forms. To geometricize, enhance, frame, and move people through the environment they subtly changed natural outlines.'

Natural-looking boulders are the most frequent objects set within borders while all extant Inka frames are made of rock. However, it is important to remember that stone does not disintegrate easily or quickly and therefore may reflect what has survived, rather than providing an accurate picture of framing trends. Perhaps there were originally many more frames made of perishable materials that have since decayed. Or in this extreme environment of natural disasters, perhaps many of these frames were destroyed or carried off by people at a later time. One may also wonder if these monuments with their bordering elements were correctly reconstructed in modern times. Still, it is valuable to analyze the framing examples that remain as important clues may emerge that can be corroborated with other material findings or with historical descriptions that further our understanding of Inka world views.

One of the most common types of Inka frames are the low-lying walls that surround boulders, such as with the 'Sacred Rock' at

The second part is from a review of the book "The Sacred Landscape of the Inca: The

Brian S. Bauer.

"Ceque is the Quechua (Inca language) word for line or border, and the ceque system in the region of the Inca capital of Cusco can best be visualized as a series of lines radiating out from

In the Quechua language, huaca means anything out of the ordinary in the natural world; whether outstandingly beautiful or outstandingly ugly. Mountain tops, funny rock formations, springs; the huacas were named after their characteristics. The translated names of the Cusco huacas are evocative as heck and include Many Colored Hill,

How relevant are these quotations to the topic of the enigmatic stonework of the northeast and mid-Atlantic U.S.? Hard to say. But we can't say we understand what these sites meant and mean to the people who built them if we don't learn to see with different eyes. And maybe these cultures have more in common than we know.